[Tilt] Shifting Gears

Architectural photography is a peculiar specialty niche.

The gear is different, the subjects are different, the lighting is different from most other kinds of photography. We recently purchased a new piece of kit for our architectural photography: a Tilt-Shift lens.This is a magical tool that does not one, but two different tricks (tilting and shifting) that the average lens can't. The shift trick is what I'm going to talk about today (I'll get into the tilting component another time). 'Shifting' refers to the lens moving up/down or left/right, while remaining in the same plane as the sensor.

Canon 17mm TS-E f/4.0 L (photo credit: Canon.com)

Antique bellows-style camera (photographer unknown)

The origin of this strange behavior goes back to the early days of photography, when the lens was attached to the film holder (and light kept out) by a "bellows" -- kind of an accordian-shaped black flexible connector. This allowed the front lens to move independently from the film-holder (but critically, in the same plane as the film).

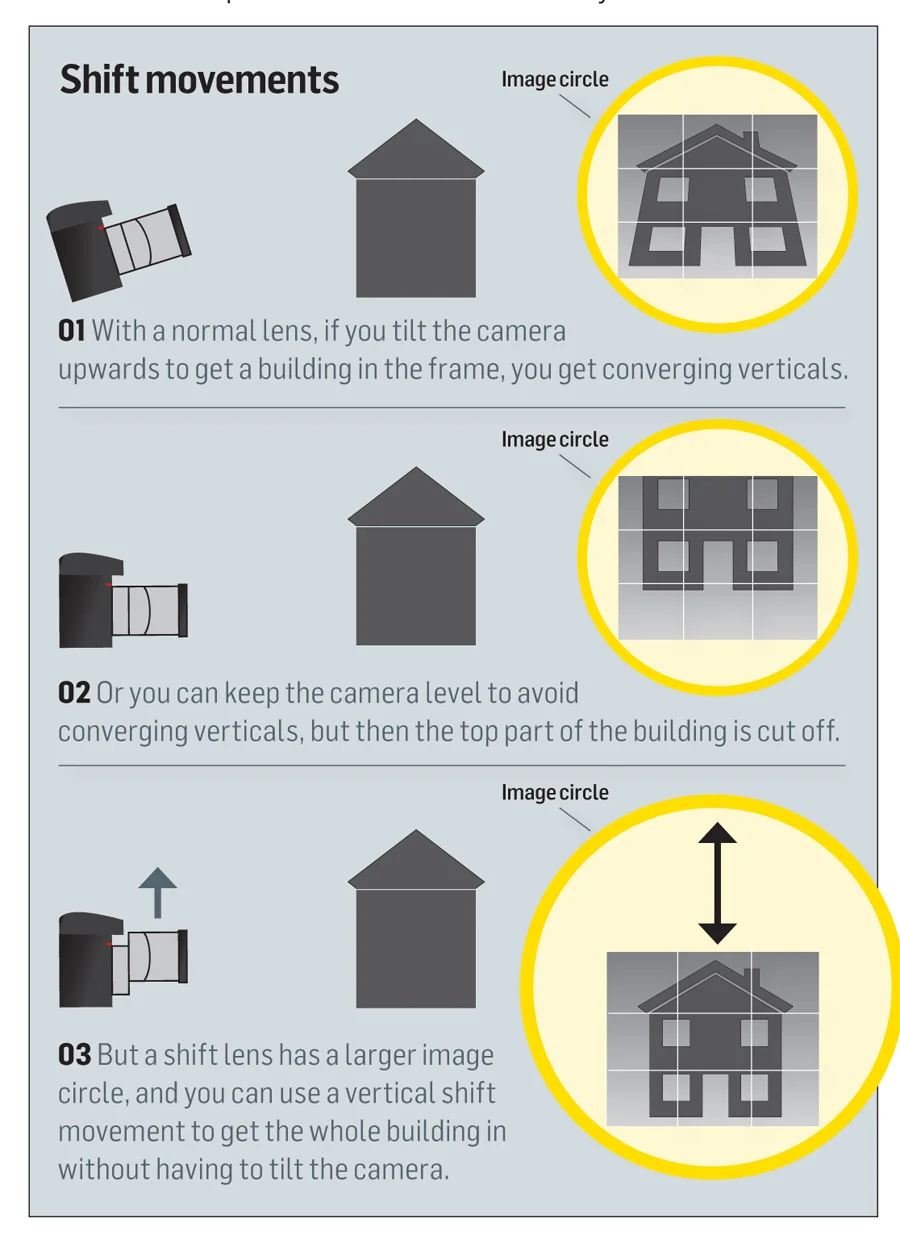

The advantage of this shifting action becomes clear when you want to photograph a tall building from ground level. As anyone who's wandered the streets of Manhattan knows, the only way to see (or shoot) the top of a tall building is to tilt your head (and your camera) back and look up. This perspective immediately creates the familiar converging-lines, making a tall, rectangular building look more like a pyramid.

(Image: designyourway.net)

However, a shift lens allows you to slide the lens upward, parallel to the plane of the sensor, meaning that the camera is looking up without tilting up -- a little bit like how a periscope works. This means that the vertical lines remain truly vertical and parallel, and don't converge. You may recognize this iconic photo of the Flatiron Building (almost certainly shot with a bellows camera), which is an excellent example of this phenomenon.

(photographer unknown)

We've only had our tilt-shift lens for a few weeks, and we haven't had many assignments yet that can take advantage of this powerful tool. However, when I went to New York a couple of weeks ago, I had a couple of hours to play. I was visiting a friend's office in midtown, so I shot a photo of her company's new building, which is across the street from the New York Public Library.

Photo: ©MacbethStudio.com

I also had time to walk a few blocks to the iconic St. Patrick's Cathedral. The scaffolding had recently come down after a multi-year, $175-million renovation project, so this was a good time to capture it. I was all the way back against the buildings on the other side of the street to get this shot, and needed every bit of the 17mm wide-angle to get the tops of the spires in the shot. But you can see -- even though the spires come to a point -- how everything remains vertical and non-converging.

Photo: ©MacbethStudio.com